Story by Steve Frankham

All photos by Steve Frankham except where specified

We’re walking through the fields of the Bunong indigenous people in Cambodia’s far eastern highlands. The sky is a cloudless electric blue, the sun hot and unforgiving, the earth on the trail beneath our feet, a striking rusty red. We follow our Cambodian guide, Torn, to the edge of a deep river canyon. Unlike the agricultural landscape surrounding us, the valley is still cloaked in its original native vegetation, a blanket of lush green tropical forest. Down there, in the valley, we have an appointment with a couple of very special local residents.

INTO THE FOREST

THE SEARCH

We begin our steep descent into the valley. Soon, we’re engulfed by the forest canopy. The air cools in the shade, and the thrum of insects fills the air. We reach the rushing, gurgling, crystal waters of the river, fringed by impressive strangler figs and buttressed silk cotton trees. It is a supremely tranquil spot, with a small house of a local Bunong family. One young man, Mr Pleav, joins us, and then we keep moving, crossing the river on a rickety wooden bridge and climbing up into the forest on the far bank. Dinner plate sized piles of poop tell us we must be close.

ELEPHANT ETIQUETTE

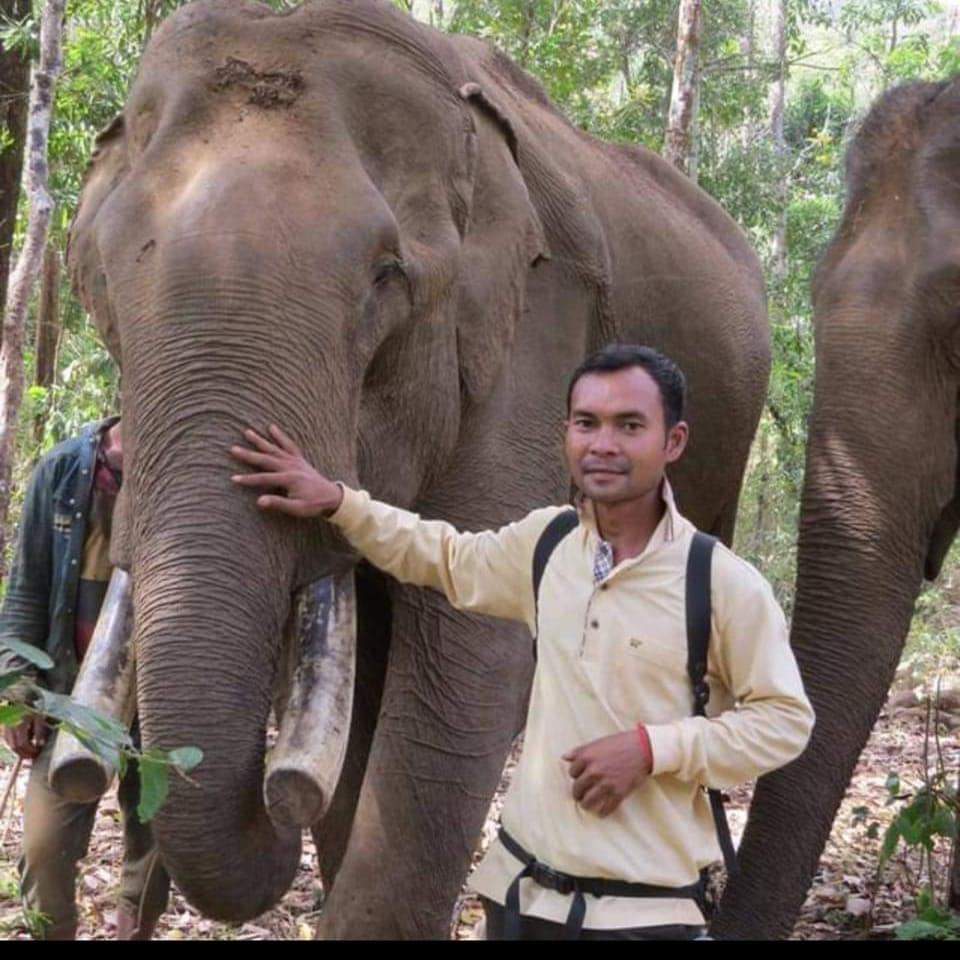

We stop, and Torn explains what the locals demand of our etiquette: stay several metres away, no sudden movements, and the residents always have the right of way! We’re given a bunch of bananas each to present to our hosts, as a sign of goodwill. Mr Pleav gives a repeated whooping call into the forest. At first, there is only silence, but then we hear the sounds of movement, the occasional crack of a branch snapping, unable the resist the sheer muscular force approaching. Then they materialize out of the forest, the great grey forms of two adult Asian elephants.

MEETING THE LADIES

These two ladies are G Bang, who’s 37, and the much larger Happy Lucky, at 52, the wise dame of the two. Torn informs us that they are inseparable best friends. As they march slowly but confidently towards us, the group falls silent in awe. They greet Torn and Mr Pleav first, familiar faces, then their attention turns to us, and the gifts we carry.

AN OTHERWORLDLY EXPERIENCE

I step forward as Happy Lucky moves towards me. I’m dwarfed by her towering form. One banana at a time, I offer my gifts, as her trunk reaches out towards me, almost like a serpentine beast, separated from the rest of the elephant. I feel the rough, dusty skin of her trunk rub up against my hand, contrasting with the moist, sensitive tip, which grabs each Banana gently and firmly, transporting it to her mouth. It’s an otherworldly experience. Once my bananas are finished, she loses interest in me, moving to another bearer of gifts.

Soon, all the treats are eaten, and the couple’s interest wanders. G Bang strolls across to a fallen tree with its trunk at exactly the right height for a satisfying belly rub, rocking backwards and forwards on the wood. This is a perfect solution to reach those hard-to-get-to spots. She then heads off after Happy Lucky, into the forest. There’s no doubt who’s the boss here, and I’m forced to step out of the way to let her pass.

A WINDOW INTO ANOTHER WORLD

The elephants head into the forest, and we follow at a respectful distance behind. We observe them as they go about their lives, stopping to munch from a particularly tasty bush or fruiting tree. It’s a great privilege, just following, watching, these magnificent, intelligent beasts, to have a window into their lives. All the time, G Bang and Happy Lucky talk to each other in a range of deep rumbles, trumpets, and snorts. Many of these sounds are too low for the human ear to pick up, but these sounds can travel over 10 kilometers, the elephant version of a mobile phone. We may never understand this language, but its importance to the elephants, highly social beings, is obvious.

We head slowly down to the river, back to the family hut where the Bunong family, tasked with maintaining this section of forest, live. We recross the river, watching the thirsty elephants grab a drink, before heading to the house for a bit of lunch and R&R as well. The elephants are free to wander wherever it pleases them, but they hang around, having a bit of a ‘standing’ nap after the morning’s wanderings. Downstream, some other members of the community are bathing water buffalo.

THE ELEPHANT COMMUNITY PROJECT

While we have a drink and wait for lunch, Torn takes the time to explain how the project works and its benefits, for the community, the elephants, and the environment. G Bang and Happy Lucky are both ‘rescue’ elephants, unlike the wild cousins, who still roam the forests of Mondulkiri Province, close to the border with Vietnam. Another male elephant also calls this valley home, however, he is in ‘musth’, a sexually charged state of elevated testosterone levels, which can make males dangerous to be around…Therefore, he has been moved to another part of the forest for the time being.

BENEFITS FOR ALL

Eco-tourists, like the small international group around me today, pay to visit the elephants and spend time with them in the forest. This allows the community to be paid a good wage, both to look after the elephants and the environment of the valley. Clearing the forest is not allowed here, so this also benefits the local wildlife. All in all, it’s a win for everyone involved: there’s local jobs, elephants able to live well in a natural environment, and happy, environmentally conscious tourists.

Mondulkiri, the least densely populated province in Cambodia, is famous for this ‘elephant-focused’ tourism. Tourism is pretty much the only reason international travellers make the long journey out to this remote corner of Cambodia. Businesses, such as bars, restaurants, and hotels, also benefit in the province’s rather scraggy capital, Sen Monorom.

THE RAID

Dinner arrives, and we’re all tucking into rice and curry when a serpentine trunk makes an appearance, brushing past my side, searching for a tasty morsel! It appears G Bang and Happy Lucky also have designs on our dinner! It’s an amusing encounter, and I can honestly say it is the first time I’ve had my lunch crashed by an elephant! A few forceful words from Torn and the family keep our elephant friends at bay, although this highly resourceful pair do find where a bag of extra bananas is stashed, and they stage a raid! It’s one of the most amusing and memorable lunches I’ve had!

After lunch, we chill for half an hour, during which time I’m once again visited by the curious pair of ladies while swinging in my hammock. They accidentally pee on my companion’s shoes (and elephants pee a lot)!. Then it’s time for a swim. The elephants head into the river for a dip, the local guide encouraging them in, and we follow. The river is cool but not cold, and marvellously refreshing.

SWIMMING WITH ELEPHANTS

Happy Lucky playfully submerges herself and surfaces beside me. With her vast bulk, she could easily crush me like a leaf on the forest floor. I proceed to give her huge rough-skinned head a scratch and a message, which she seems to enjoy.

A MOMENT TO SAVOUR

I’m conscious elephants need their own time, so I float off into the current, lying on my back, feeling the cool water flowing around me. I take in the sky framed by the lush jungle on either side of the river. From this perspective, the jungle looks pristine, endless. You could forget that this is just a small island of forest, surrounded by a sea of humanity. I reflect on the amazing experience and privilege of sharing this jungle pool, and this day, with these great beasts. It’s not something I will forget.

We dry ourselves off, say goodbye to the Happy Lucky and G Bang, say goodbye to this forest, and hike out of the valley, back into the human world. I glance back at this part of the forest that survives only because of the presence of the elephants.

PUTANG VILLAGE

We head to Putang Village, to experience a little of Bunong community life. The village is a laidback, easy-going rural place. Pigs lie comfortably in their dust baths, chickens strut around the houses. Behind the houses, tied up in the field are water buffalo, the workhorses of the community.

The blocky nature of Cambodian houses contrasts against the low, elegant form of a traditional Bunong longhouse, its grass roof, and bamboo walls echoing the forms of nature. We hunch down and step into its cool interior. Inside, a group of older Bunong ladies are chattering away, amused to see these visitors from a different world. They’re friendly and cheerful. The open space inside, with seating facing into the centre, seems to encourage communal living and cooperation. It reminds me of longhouses in Borneo and the Amazon.

A CULTURAL REVIVAL?

Torn explains, ‘This kind of house had stopped being made, as people switched to the ‘Cambodian’ style that makes up 99% of country residences. But these longhouses attract tourists looking to experience the traditional Bunong culture.’ Now, many people are considering building houses in the traditional style. This may be to attract income from tourism, but it is also something of a ‘cultural’ revival. Traditional methods of building are being rediscovered by a new generation, and perhaps a new pride in the Bunong way of life!

Saying goodbye to our friendly hosts, we emerge back into the light. In the shade of a house an older gentleman, his skin wrinkled by the sun, but obviously still lithe and strong, is weaving a traditional fishing net. We ask how long he has been working on this, to which he replies several weeks. The old ways of living are not dead yet, and the world is a richer place for that. We leave Patang behind and return to Sen Monorom, reflecting on a rich and remarkable day.

THE VANISHING WILDERNESS

Mondulkiri Province is still home to a large proportion of Cambodia’s rapidly disappearing forests. Cambodia is a country blessed with huge biodiversity and rich natural resources, but it is also notorious for having one of the highest deforestation rates in the world, uncontrolled poaching, and wildlife crime. Cambodia’s wild is disappearing.

SILENT FORESTS

Of the forests that remain, many are being emptied of their wildlife due to the ubiquitous use of ‘wire’ traps throughout the forest. Wire traps snare the legs of any animal that is unfortunate enough to pass by, regardless of whether it is the targeted species or not. Any beast, from a mouse deer to a wild elephant, will be caught by these brutal homemade devices. Once trapped, they are doomed to an agonizing death that may last days or even weeks. It is estimated that the forests of Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia are littered with more than 12 million wire traps. These deadly devices are silencing Cambodia’s remaining forests.

SEIMA PROTECTION FOREST

I wanted to see for myself what these remaining forests are like, and whether it is possible to save them. I talked to Torn, and we arranged to visit one of Cambodia’s most precious remaining tracts of forest…the Seima Protection Forest. Seima, covering about 3000km of rainforest, monsoon forest, and grasslands, is perhaps the most biodiverse protected area in Cambodia. It is home to 7 primate species, including the world’s largest population of black-shanked douc langur, and a healthy population of yellow-cheeked gibbons. We set off an hour before dawn the next morning, driving through the pre-dawn chill in a rickety tuk-tuk.

THE GIBBON’S SONG

Turning down a dirt track as the sun rose above the hills, we were met by Ngong, a local ranger in Siema, and headed into the forest. Although not far from the main road to Sen Monorom, we were soon enveloped in the thick rainforest. Giant knarled strangled figs and silk cotton trees rose like cathedral columns above us. Ngong, obviously knowing the forest like the back of his hand, froze on the track, and sure enough, soon we heard the haunting whooping call of yellow-cheeked gibbons echoing through the forest. Although we failed to catch a glimpse, their presence in the forest was inspiring.

Other signs hinted at the deep problems facing conservation in Seima, and Cambodia as a whole. Several times we came across the freshly cut stumps of illegally cut teak trees, a rare and valued red hardwood, favoured for high-quality furniture and construction.

THE DISAPPEARED

Another alarming point was the lack of tracks or animal sign on the forest floor. Even in protected areas such as Seima, hunting is rife, both with guns and wire traps. While largely arboreal species such as gibbons may be able to survive, the forest is being stripped of its terrestrial wildlife. Tigers were last seen in Cambodia in 2007, and a couple of years ago, Leopards followed them into local extinction (the same has happened in Laos and Vietnam). This is a tragedy for Cambodia’s natural heritage. Even if tigers and leopards were somehow ‘reintroduced’ into forests like Seima, there would be little left for them to eat. Native wildlife like the gaur, a giant forest buffalo, and banteng have almost certainly been lost from Seima, as have critical prey species like sambar deer. Even wild pigs are in steep decline. It’s a grim picture.

ECO-TOURISM AND OPPORTUNITY

The only large mammal we spotted was a giant black squirrel, feeding happily in the treetops. It’s still possible to restore Seima to its former glory. The area has huge potential for eco-tourism, which Torn is anxious to promote. If handled well, this could provide jobs and income to this beautiful area, while also enhancing its protection. The presence of eco-tourists often acts as a deterrent to hunters, leading to an increase in wildlife populations. Many former hunters could be employed as rangers, making a living protecting species, rather than pushing them to extinction.

A MISSED OPPORTUNITY

The restoration of habitat and re-introduction of ‘megafauna’ such as leopards and tigers would be a powerful draw for tourists from across South East Asia. Regardless of the possibilities, the government seems wilfully ignorant of Cambodia’s eco-tourism potential. Investment in eco-tourism is being stifled by the authorities and overly complex bureaucracy. I feel this is a tragic missed opportunity, both for local people, wildlife, and the country as a whole.

Valuable teak and rosewood trees take decades to grow to a harvestable size, and wildlife, when hunted unsustainably, will disappear entirely, meaning two key resources for local people will vanish. Eco-tourism can provide a permanent income to local communities and provide a draw for tourists from across the region. Many tourists already come to this region for the Elephant Project, so the market for wildlife experiences is already in place.

We were picked up by our tuk-tuk driver on the road. As I headed back to Sen Momorom, I reflected on both the beauty of the forest and the critical threats facing Cambodia’s natural environment. The situation is dire, and there seems to be little political will to change things.

SAM

On my last day in Sen Monorom, I met up with Sam Nang, my intelligent, understated host. Sam is the founder of the Elephant Community Project and the owner of the beautiful Greenhouse Resort, on the outskirts of the town.

Sam used to work for WWF in Cambodia, before quitting to set up the elephant project. I asked him how this happened, and the answer provided an insight into Cambodia’s environmental woes…

“One day I was patrolling the protected area, and I came across a man illegally logging in the forest. It was my job to stop this. The man said to me, ‘Why are you arresting me? I’m just cutting one tree so I have enough money to feed my kids, to support my family! The government allows wealthy foreign companies to open commercial logging concessions, and hugely destructive bauxite and gold mines! These mines make the already rich richer – that’s legal. But I’m not allowed to cut a tree to feed my family!’ I let him go. I thought about what he said, and quit soon after. I wanted to get into environmentally friendly tourism and a business that could provide local people with a good living, without destroying the environment. Hence the Elephant Community Project.”

WHY NOT CAMBODIA?

We discuss why the government is so unsupportive of eco-tourism in Mondulkiri, and Cambodia as a whole. I mention successful projects I have witnessed, such as the growth of environmentally friendly tourism in Costa Rica, gorilla and safari tourism in Africa, and tourism run by indigenous communities in South America and worldwide.

Sam sighs tiredly ‘I wish you could have a meeting with the people in government and tell them this message, but I don’t think they’re interested in listening.’

I talk more specifically about tourism in Mondulkiri Province and in Sen Monorom. ‘‘The only reason tourists come to Sen Monorom is because of the elephant project, the wildlife, and the connection with nature. Sen Monorom is basically a scruffy frontier town. No one is going to come here for the architecture (for that, people head to the magnificent temples of Angkor, near Siem Reap). There’s no Eiffel Tower. Lose the nature, and no one will come; protect the forest, the wildlife better, and more tourists will come. Nature could provide a long-term, sustainable future for the community.”

A COUNTRY FOR SALE

Sam agrees, but notes that for many members of the government, helping the community and preserving this country’s beautiful environment is simply not a priority. They are just focused on personal gain and selling off their country’s resources as quickly as possible. “They’re not interested in helping Cambodia. They just want to make money and send their children to posh universities in the UK.”

A BRIGHTER FUTURE?

Driving towards Sen Monorom the week before, I remembered passing hundreds of logging trucks, stacked to the brim. They were heading towards Phnom Penh and the coastal ports. Much of the wood might be from legal plantations, but illegally cut hardwoods are often buried beneath. A land of green, vibrant forests is being stripped and replaced by a dusty, degraded agricultural landscape. It’s a brutal thought. As in many poor countries, people are forced to do anything they can to survive on a daily basis, even if those actions are destroying the prospects of the next generation. Cambodia is a land with so much beauty and so much potential, but besieged by problems.

Sam, Torn, and the eco-tourism operators and environmentalists of Mondulkiri give me hope that perhaps a better, more thoughtful, sustainable vision for Cambodia is possible. They are a ray of sunlight on Cambodia’s stormy environmental horizon.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank both Sam Nang and Torn (Chantorn Thea) for their help with this article. Without their assistance and deep local knowledge, this article would not have been possible. I would also like to thank the welcoming Bunong people of Putang village.

I would also like to thank Ngong, for his guiding skills and patience in Seima Protection Forest.

Sam is founder of the Elephant Community Project, which runs highly recommended ethical elephant community tourism in Mondulkiri.

Chantorn Thea runs trekking and wildlife trips in the Seima Protection Forest and beyond. He can be contacted at:

Trekking Cambodia, Mondulkiri Gibbon and Wildlife Safari | Elephant tours

Likewise, I can also lead and organise conservation and wildlife trips throughout the region. For private tailor made tours please contact me on: lacandongringo@yahoo.com

Fantastic! This beautifully illustrates the vital role of ecotourism in elephant conservation in Cambodia and powerfully highlights how this approach benefits local communities, paving the way for a brighter future. Reading this inspiring piece makes me long to revisit Cambodia and experience this positive impact firsthand. Great job, Steve!

Thanks mate, much appreciated!